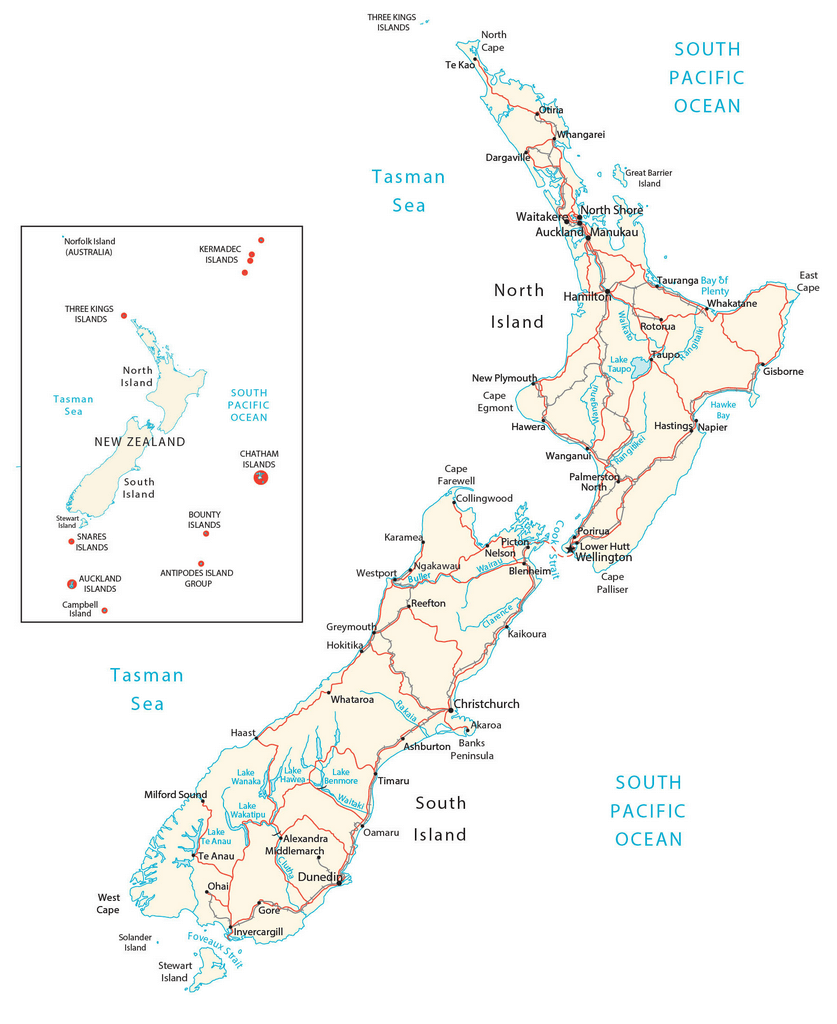

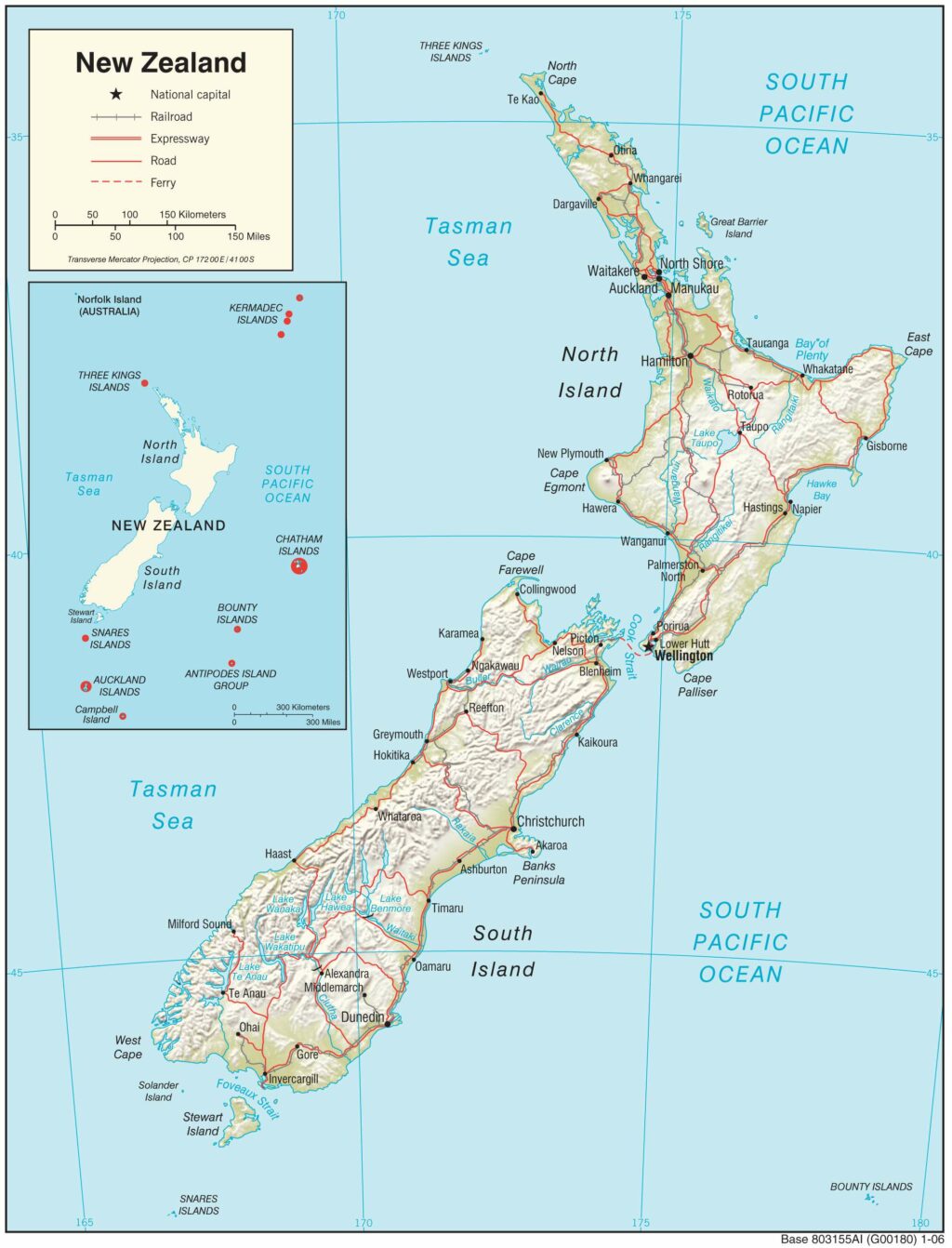

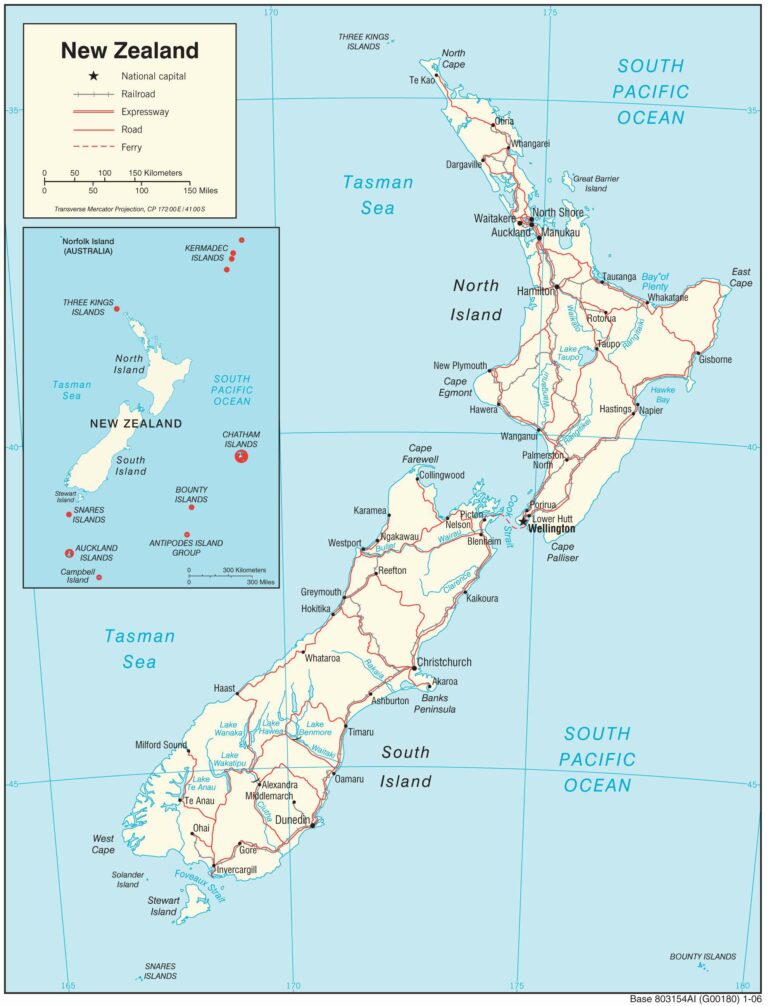

Covering a total area of 268,021 sq.km (103,483 sq mi), New Zealand is comprised of two large islands that can be observed on the physical map of the country above – the North Island and South Island (which are separated by the Cook Strait), as well as Stewart Island, hundreds of coastal islands and about 600 small regional islands.

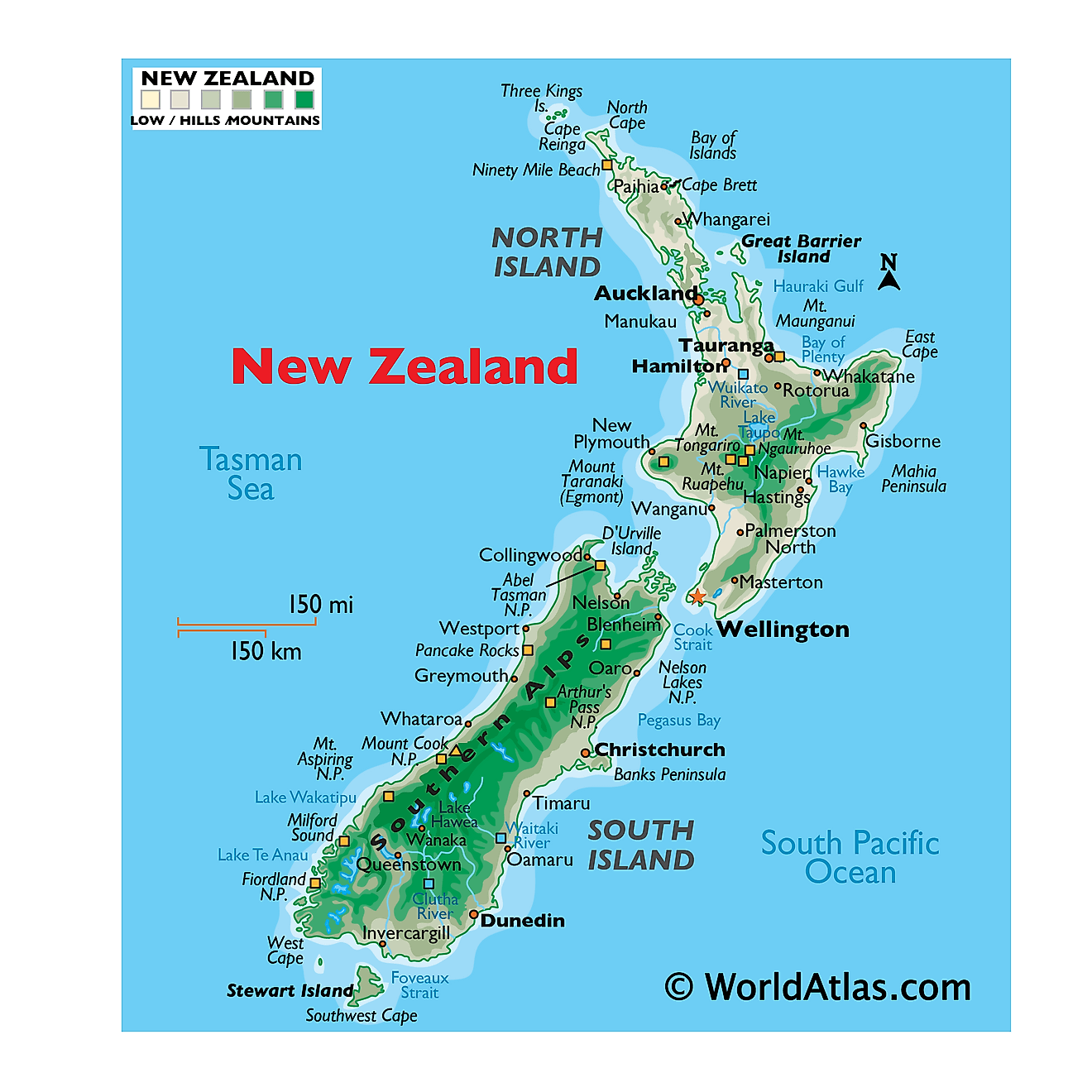

From north to south, New Zealand is a country of snow-capped mountains and scenic landscapes. Positioned along the Ring of Fire, the Southern Alps (and its many ranges) extend through the western portions of South Island. As marked on the map by an upright yellow triangle, the country’s highest point, Mount Cook (Aoraki) is located in the Southern Alps, as well as over 350 glaciers and a wide assortment of national parks. Mount Cook rises to an elevation of 12,316ft (3,754 m). Throughout the Southern Alps, an additional 19 mountains rise above 10,000 ft (3,000 m). Along the western side of these massive peaks there’s a narrow strip of coastline. Along their eastern flank, the mountains slope into a region of rolling hills and plains, drained by glacier-fed rivers.

In the far south, within the confines of Fiordland National Park, a jagged coastline of fjords, inlets and bays front the Tasman Sea. Milford Sound – located within the park, is surrounded by sheer rock faces that rise to 3,937 ft (1,200 meters) or more on either side. It’s widely considered New Zealand’s top travel destination.

The mountains found on North Island are volcanic in nature, and many remain quite active. On the island’s southwestern corner, Mount Taranaki (or Mt. Egmont) rises to an elevation of 8,261 ft (2,518 m). Other volcanic peaks of note stretch across a wide central plateau, including Mount Ruapehu (2,797 m/9,177 ft), Mount Ngauruhoe (2,291 m/7,515 ft), and Mount Tongariro (1,968 m/6,458 ft). This thermal belt area is replete with boiling mud pools, geysers, hot springs and steam vents.

Broad coastal plains ring much of North Island, and along its central western coastline, limestone caves, caverns and underground rivers are common. Along the north eastern coastline, the Bay of Islands is famous for its 125 (or more) scenic islands and secluded coves. With Mount Maunganui guarding the entrance, and nearly 62 miles (100 km) of white sand, the Bay of Plenty is New Zealand’s premier beach area.

Large areas of temperate rain forests are found along the western shore of South Island, and across much of New Zealand’s North Island.

Occupying an extinct volcanic crater, the country’s largest lake is Lake Taupo on North Island. The country’s longest river, the Waikato, flows north from Lake Taupo through Hamilton, and on into the Tasman Sea. Lake Te Anau is the largest lake on South Island. The Clutha River is the island’s longest river, and like most rivers here, it originates in a Southern Alps glacial lake. The lowest point of New Zealand is South Pacific Ocean (0 m).

Explore the stunning beauty of New Zealand with this interactive map. View the two main islands, the Southern Alps, and Canterbury Plains in satellite imagery and an elevation map. Discover major cities, towns, regions, roads, and rivers as you explore this amazing country.

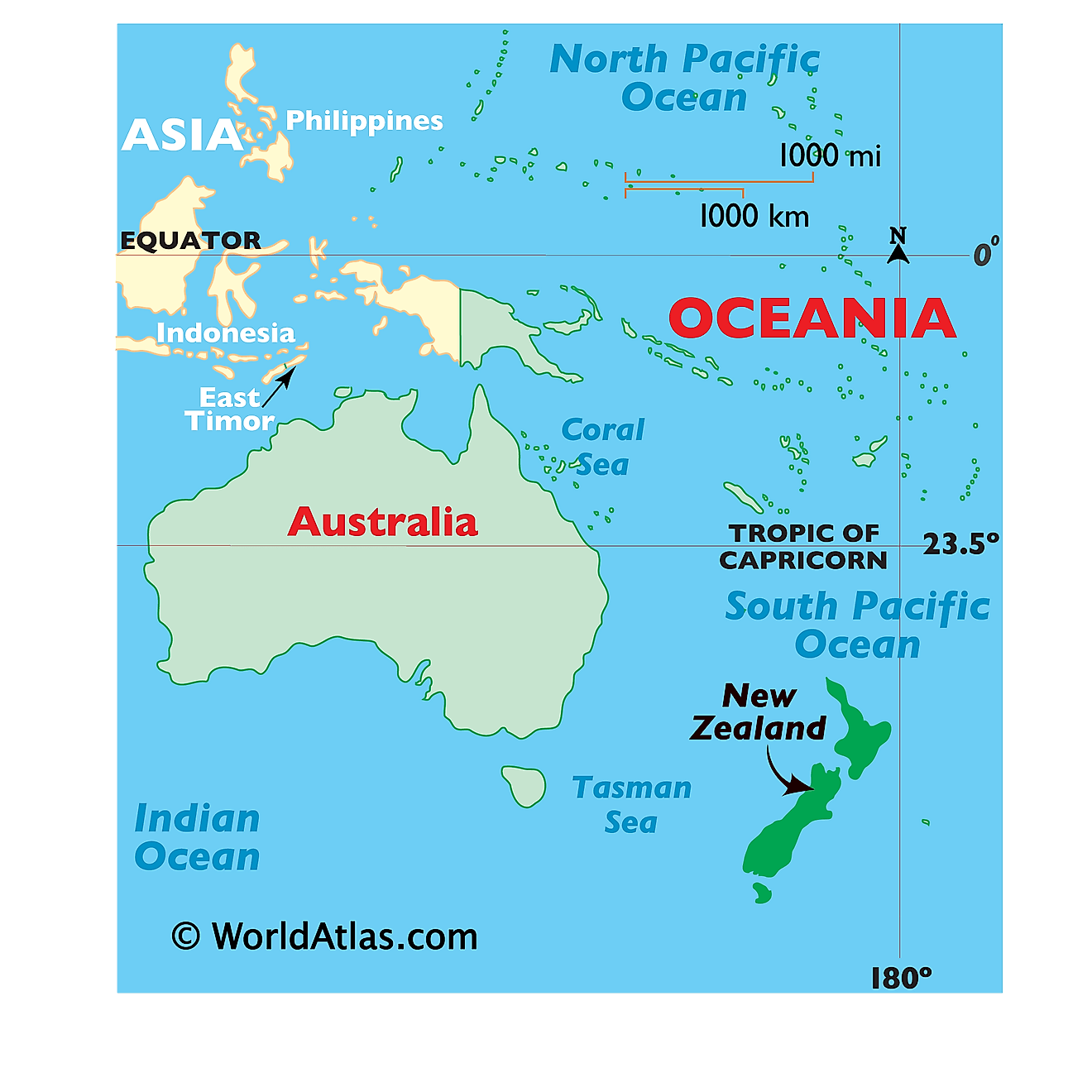

Location Maps

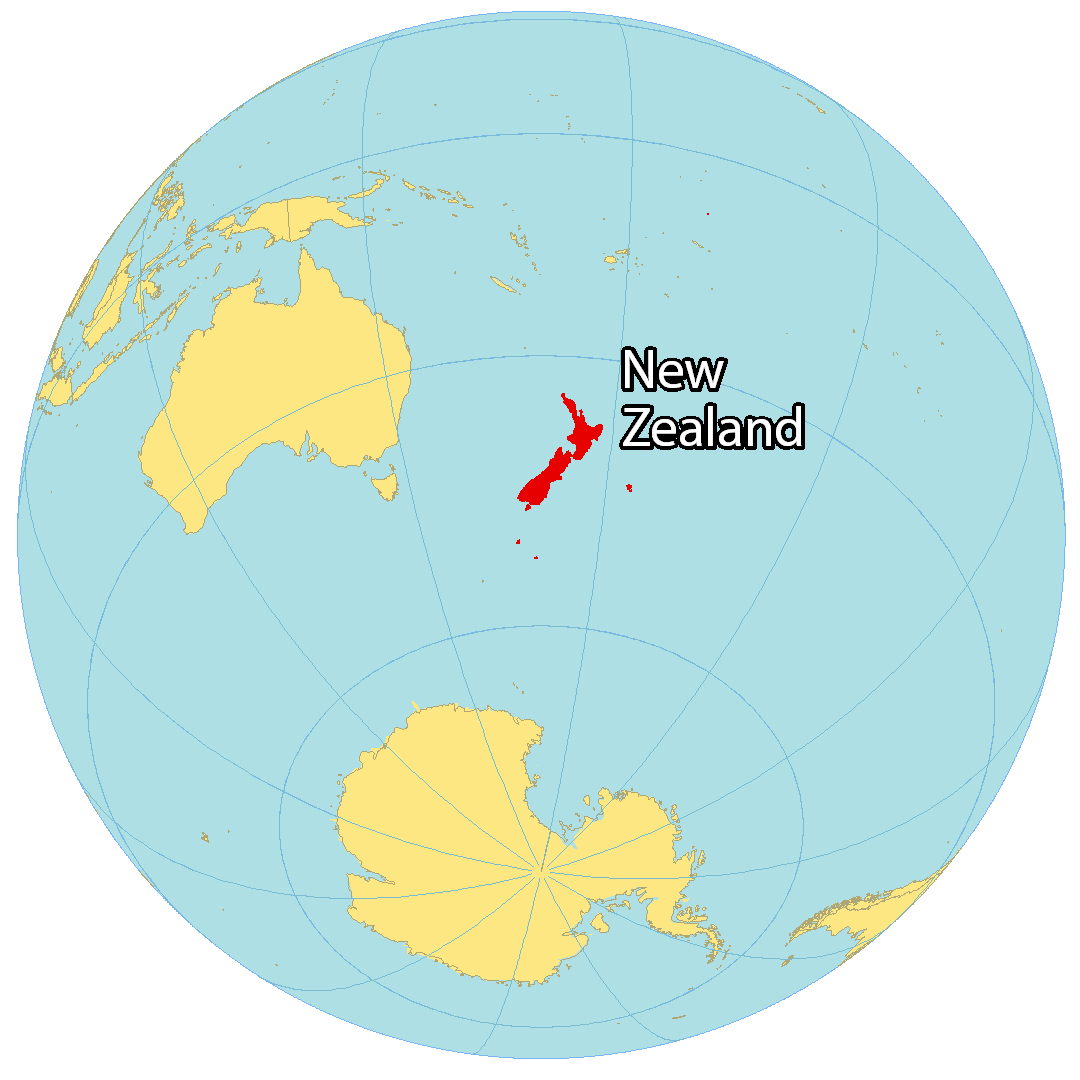

Where is New Zealand?

New Zealand is an island country in the South Pacific Ocean as part of Oceania. Famous for its rugby, kiwi, sheep, and the indigenous Maori culture, New Zealand is located to the southeast of Australia, separated by the Tasman Sea. The islands of Tonga, Fiji, Vanuatu, and New Caledonia are all close to New Zealand to the north. New Zealand is made up of two main islands – the North (Te Ika-a-Māui) and the South Island (Te Waipounamu), which are separated by the Cook Strait.

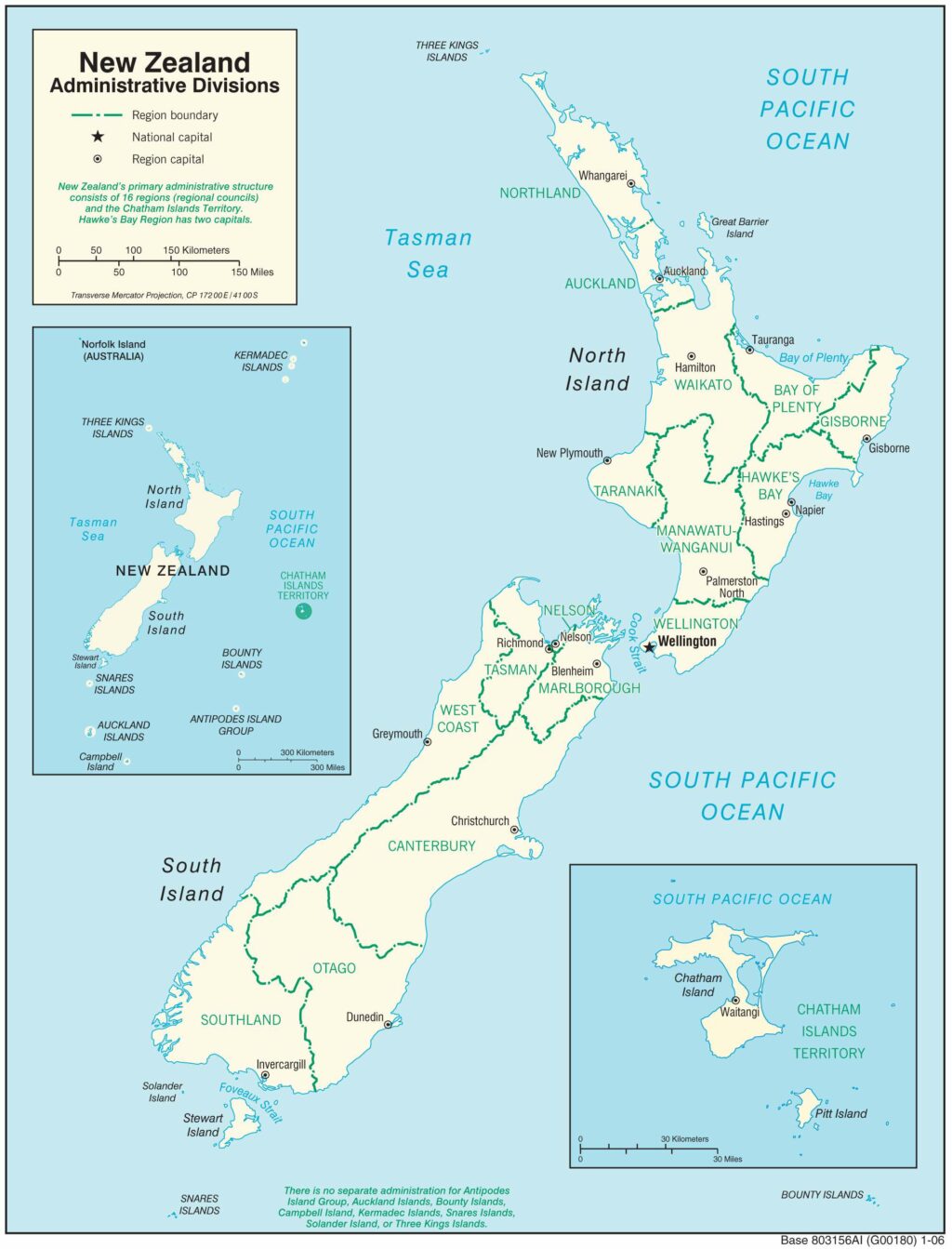

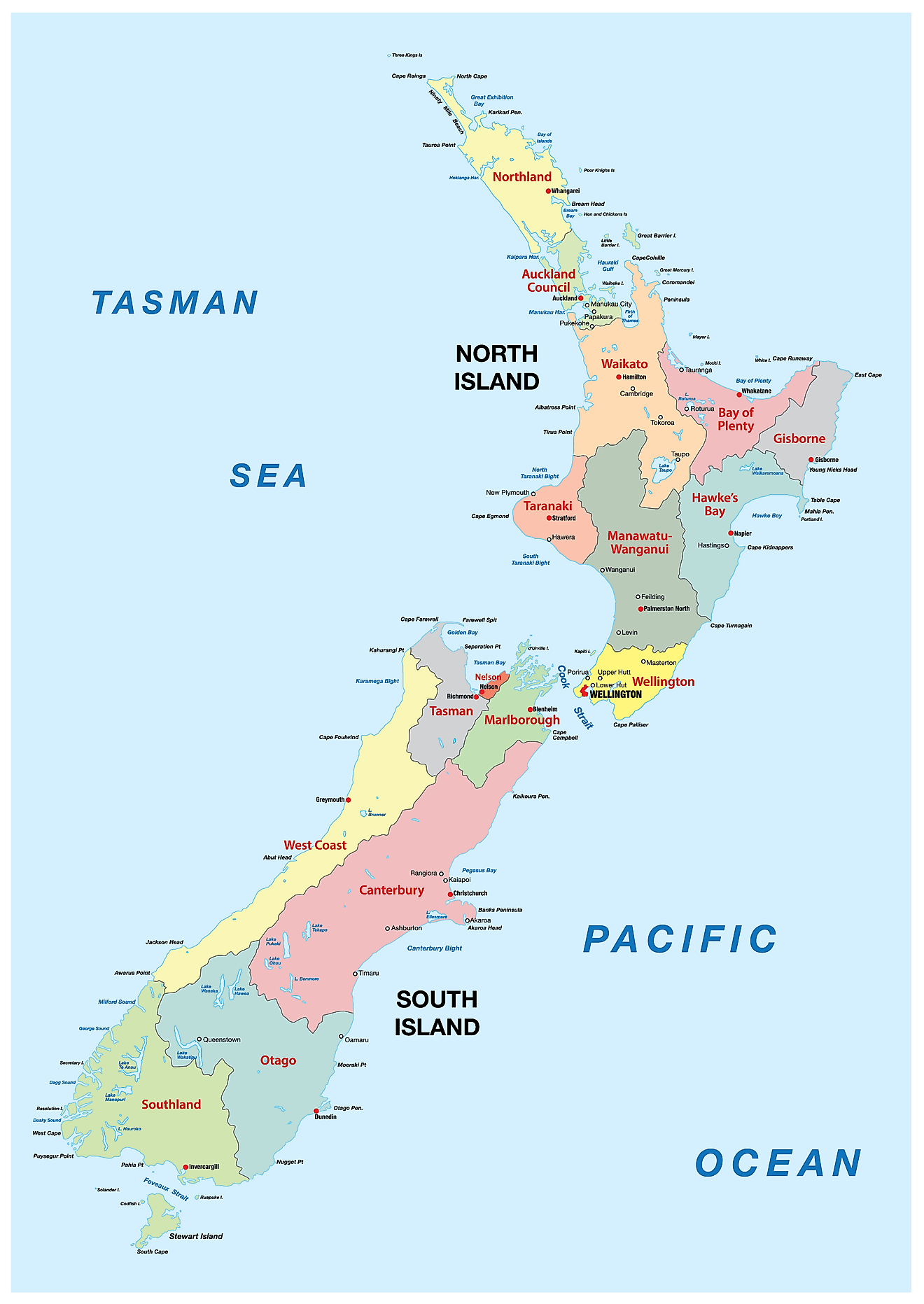

The South Island is the larger of the two islands, though less populous, containing two major cities of Christchurch and Dunedin. On the other hand, the North Island is smaller in size but more populous, with major cities like Auckland, Wellington, and Hamilton. The capital city of New Zealand, Wellington, is located on the southwest corner of the North Island.

High Definition Political Map of New Zealand

New Zealand Administrative Map

Physical Map of New Zealand

Geography

New Zealand is located near the centre of the water hemisphere and is made up of two main islands and more than 700 smaller islands. The two main islands (the North Island, or Te Ika-a-Māui, and the South Island, or Te Waipounamu) are separated by Cook Strait, 22 kilometres (14 mi) wide at its narrowest point. Besides the North and South Islands, the five largest inhabited islands are Stewart Island (across the Foveaux Strait), Chatham Island, Great Barrier Island (in the Hauraki Gulf), D’Urville Island (in the Marlborough Sounds) and Waiheke Island (about 22 km (14 mi) from central Auckland).

New Zealand is long and narrow—over 1,600 kilometres (990 mi) along its north-north-east axis with a maximum width of 400 kilometres (250 mi)—with about 15,000 km (9,300 mi) of coastline and a total land area of 268,000 square kilometres (103,500 sq mi). Because of its far-flung outlying islands and long coastline, the country has extensive marine resources. Its exclusive economic zone is one of the largest in the world, covering more than 15 times its land area.

The South Island is the largest landmass of New Zealand. It is divided along its length by the Southern Alps. There are 18 peaks over 3,000 metres (9,800 ft), the highest of which is Aoraki / Mount Cook at 3,724 metres (12,218 ft). Fiordland’s steep mountains and deep fiords record the extensive ice age glaciation of this southwestern corner of the South Island. The North Island is less mountainous but is marked by volcanism. The highly active Taupō Volcanic Zone has formed a large volcanic plateau, punctuated by the North Island’s highest mountain, Mount Ruapehu (2,797 metres (9,177 ft)). The plateau also hosts the country’s largest lake, Lake Taupō, nestled in the caldera of one of the world’s most active supervolcanoes. New Zealand is prone to earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

The country owes its varied topography, and perhaps even its emergence above the waves, to the dynamic boundary it straddles between the Pacific and Indo-Australian Plates. New Zealand is part of Zealandia, a microcontinent nearly half the size of Australia that gradually submerged after breaking away from the Gondwanan supercontinent. About 25 million years ago, a shift in plate tectonic movements began to contort and crumple the region. This is now most evident in the Southern Alps, formed by compression of the crust beside the Alpine Fault. Elsewhere, the plate boundary involves the subduction of one plate under the other, producing the Puysegur Trench to the south, the Hikurangi Trench east of the North Island, and the Kermadec and Tonga Trenches further north.

New Zealand, together with Australia, is part of a region known as Australasia. It also forms the southwestern extremity of the geographic and ethnographic region called Polynesia. Oceania is a wider region encompassing the Australian continent, New Zealand, and various island countries in the Pacific Ocean that are not included in the seven-continent model.

- Landscapes of New Zealand

Rural scene near Queenstown

Hokitika Gorge, West Coast

The Emerald Lakes, Mt Tongariro

Lake Gunn

Pencarrow Head, Wellington

Climate

New Zealand’s climate is predominantly temperate maritime (Köppen: Cfb), with mean annual temperatures ranging from 10 °C (50 °F) in the south to 16 °C (61 °F) in the north. Historical maxima and minima are 42.4 °C (108.32 °F) in Rangiora, Canterbury and −25.6 °C (−14.08 °F) in Ranfurly, Otago. Conditions vary sharply across regions from extremely wet on the West Coast of the South Island to semi-arid in Central Otago and the Mackenzie Basin of inland Canterbury and subtropical in Northland. Of the seven largest cities, Christchurch is the driest, receiving on average only 618 millimetres (24.3 in) of rain per year and Wellington the wettest, receiving almost twice that amount. Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch all receive a yearly average of more than 2,000 hours of sunshine. The southern and southwestern parts of the South Island have a cooler and cloudier climate, with around 1,400–1,600 hours; the northern and northeastern parts of the South Island are the sunniest areas of the country and receive about 2,400–2,500 hours. The general snow season is early June until early October, though cold snaps can occur outside this season. Snowfall is common in the eastern and southern parts of the South Island and mountain areas across the country.

Biodiversity

New Zealand’s geographic isolation for 80 million years and island biogeography has influenced evolution of the country’s species of animals, fungi and plants. Physical isolation has caused biological isolation, resulting in a dynamic evolutionary ecology with examples of distinctive plants and animals as well as populations of widespread species. The flora and fauna of New Zealand were originally thought to have originated from New Zealand’s fragmentation off from Gondwana, however more recent evidence postulates species resulted from dispersal. About 82% of New Zealand’s indigenous vascular plants are endemic, covering 1,944 species across 65 genera. The number of fungi recorded from New Zealand, including lichen-forming species, is not known, nor is the proportion of those fungi which are endemic, but one estimate suggests there are about 2,300 species of lichen-forming fungi in New Zealand and 40% of these are endemic. The two main types of forest are those dominated by broadleaf trees with emergent podocarps, or by southern beech in cooler climates. The remaining vegetation types consist of grasslands, the majority of which are tussock.

Before the arrival of humans, an estimated 80% of the land was covered in forest, with only high alpine, wet, infertile and volcanic areas without trees. Massive deforestation occurred after humans arrived, with around half the forest cover lost to fire after Polynesian settlement. Much of the remaining forest fell after European settlement, being logged or cleared to make room for pastoral farming, leaving forest occupying only 23% of the land.

The forests were dominated by birds, and the lack of mammalian predators led to some like the kiwi, kākāpō, weka and takahē evolving flightlessness. The arrival of humans, associated changes to habitat, and the introduction of rats, ferrets and other mammals led to the extinction of many bird species, including large birds like the moa and Haast’s eagle.

Other indigenous animals are represented by reptiles (tuatara, skinks and geckos), frogs, such as the protected endangered Hamilton’s Frog, spiders, insects (wētā), and snails. Some, such as the tuatara, are so unique that they have been called living fossils. Three species of bats (one since extinct) were the only sign of native land mammals in New Zealand until the 2006 discovery of bones from a unique, mouse-sized land mammal at least 16 million years old. Marine mammals, however, are abundant, with almost half the world’s cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) and large numbers of fur seals reported in New Zealand waters. Many seabirds breed in New Zealand, a third of them unique to the country. More penguin species are found in New Zealand than in any other country, with 13 of the world’s 18 penguin species.

Since human arrival, almost half of the country’s vertebrate species have become extinct, including at least fifty-one birds, three frogs, three lizards, one freshwater fish, and one bat. Others are endangered or have had their range severely reduced. However, New Zealand conservationists have pioneered several methods to help threatened wildlife recover, including island sanctuaries, pest control, wildlife translocation, fostering and ecological restoration of islands and other protected areas.