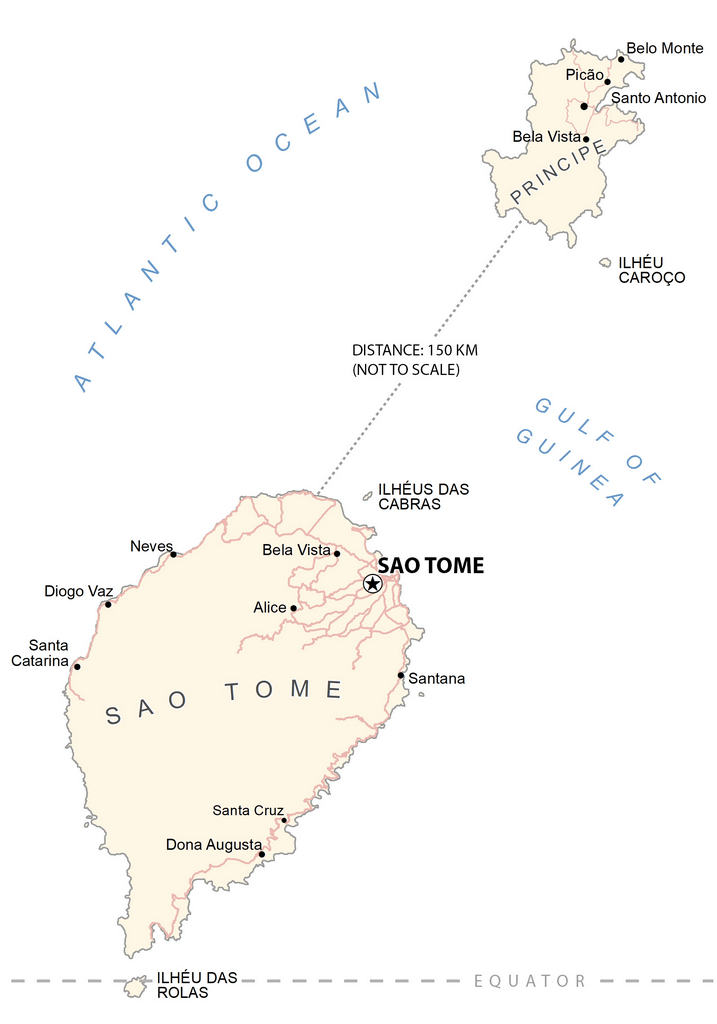

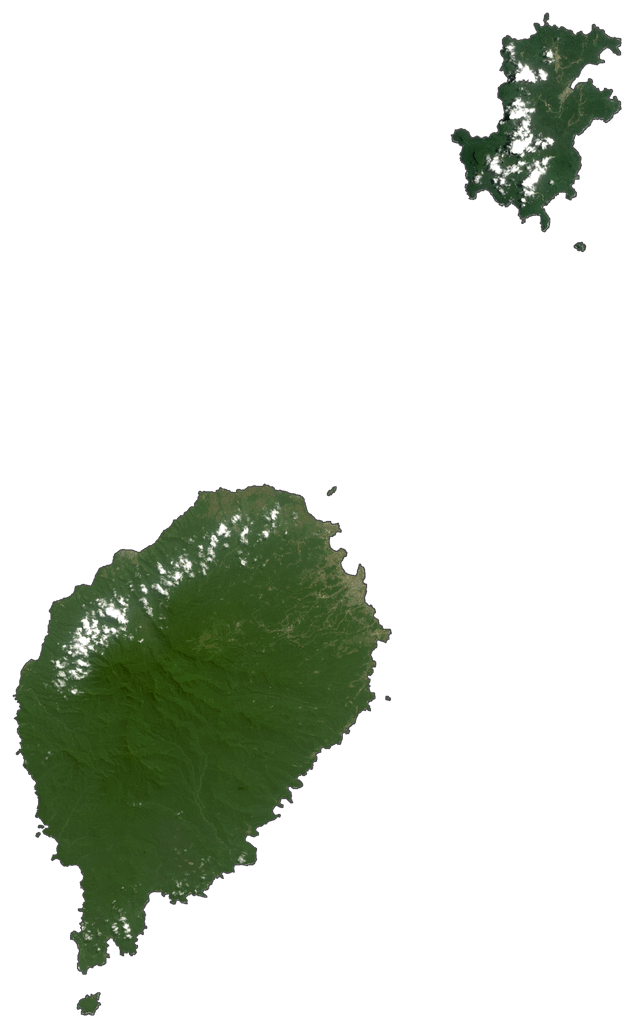

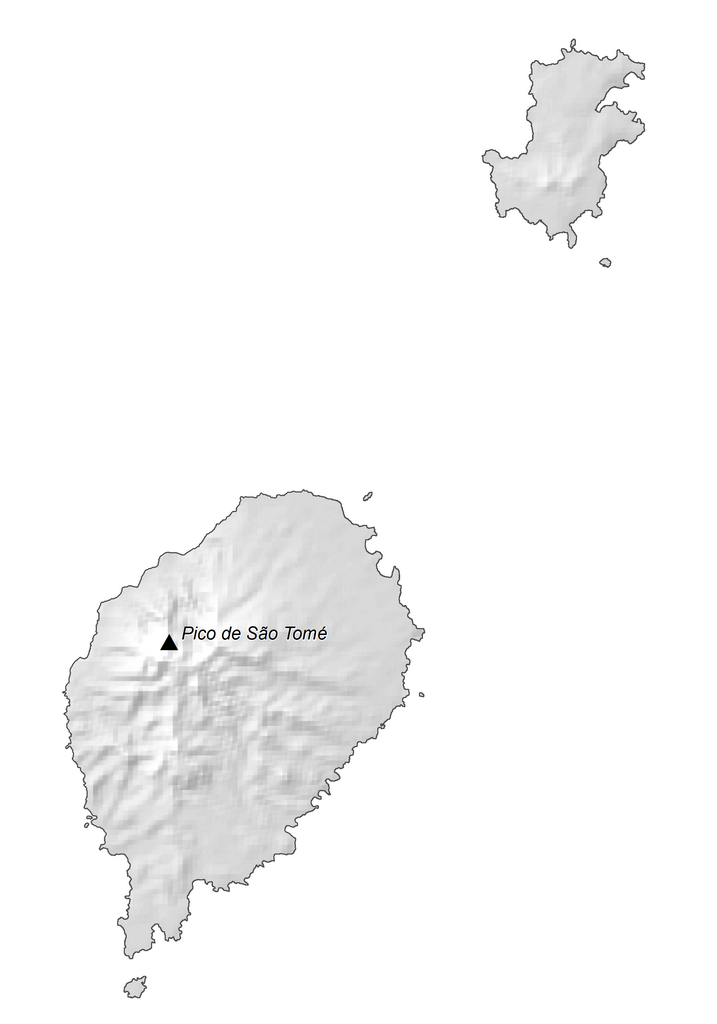

São Tomé and Príncipe, one of the smallest African countries, is located on the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean. It has a total area of around 1,001 sq. km and a coastline of about 209 km. As observed in the physical map of the country, it has two major islands, São Tomé and Príncipe from where the name of the country is derived. These islands are separated by a distance of around 181.55 km and are surrounded by many smaller islands forming archipelagos. Some of the important smaller islands have been represented on the map. All these islands are part of an extinct volcanic mountain range.

São Tomé is the largest island of the country and is located just above the equator as visible on the map above. It is more mountainous than Príncipe. The highest peak here (Pico de São Tomé) is at 2,024 m which is also the highest point in the country.

The highest point on Príncipe is at 948 m.

At 0 m, the Atlantic Ocean is the lowest elevation in the country.

Both the islands have swift streams flowing down the mountains and through forests and agricultural lands to enter the sea.

Other smaller islands observed on the map are Tinhosa Islands, Illheu das Cabras, and Illheu das Rolas. Tinhosa Islands are part of UNESCO’s Island of Príncipe Biosphere Reserve. Illheu das Cabras is a small island with two hills and a lighthouse to the northeast of São Tomé. Illheu das Rolas, located off the southern tip of São Tomé is also an uninhabited island.

Explore the lush forests and vibrant coastlines of Sao Tome and Principe with this detailed map. See the various towns, villages, roads, and bodies of water that make up the two islands. Take in the stunning satellite imagery of the forests that blanket both islands.

Online Interactive Political Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

São Tomé and Príncipe has six administrative districts. They are Água Grande, Cantagalo, Caué, Lembá, Lobata, and Mé-Zóchi. All of them are located on the island of São Tomé. The Príncipe island had only one district since 1980 called Pagué but in 1995, it was replaced by the Autonomous Region of Príncipe. With an area of 267 sq.km, Caué is the biggest district in the country but the least populous one. Covering only 16.5 sq.km, Água Grande is the country’s smallest district but the most populated one. Its capital São Tomé is also the national capital.

Location Maps

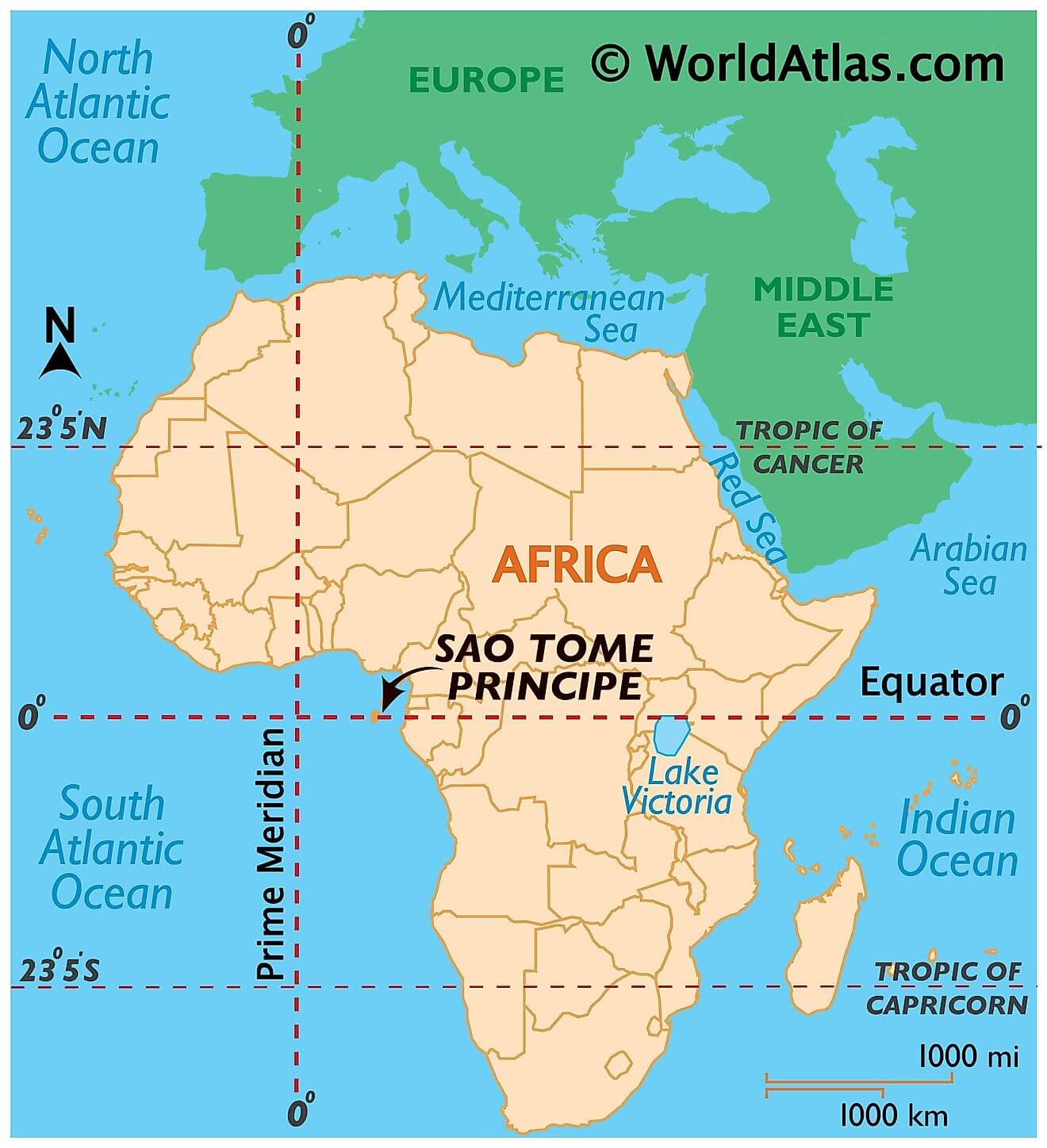

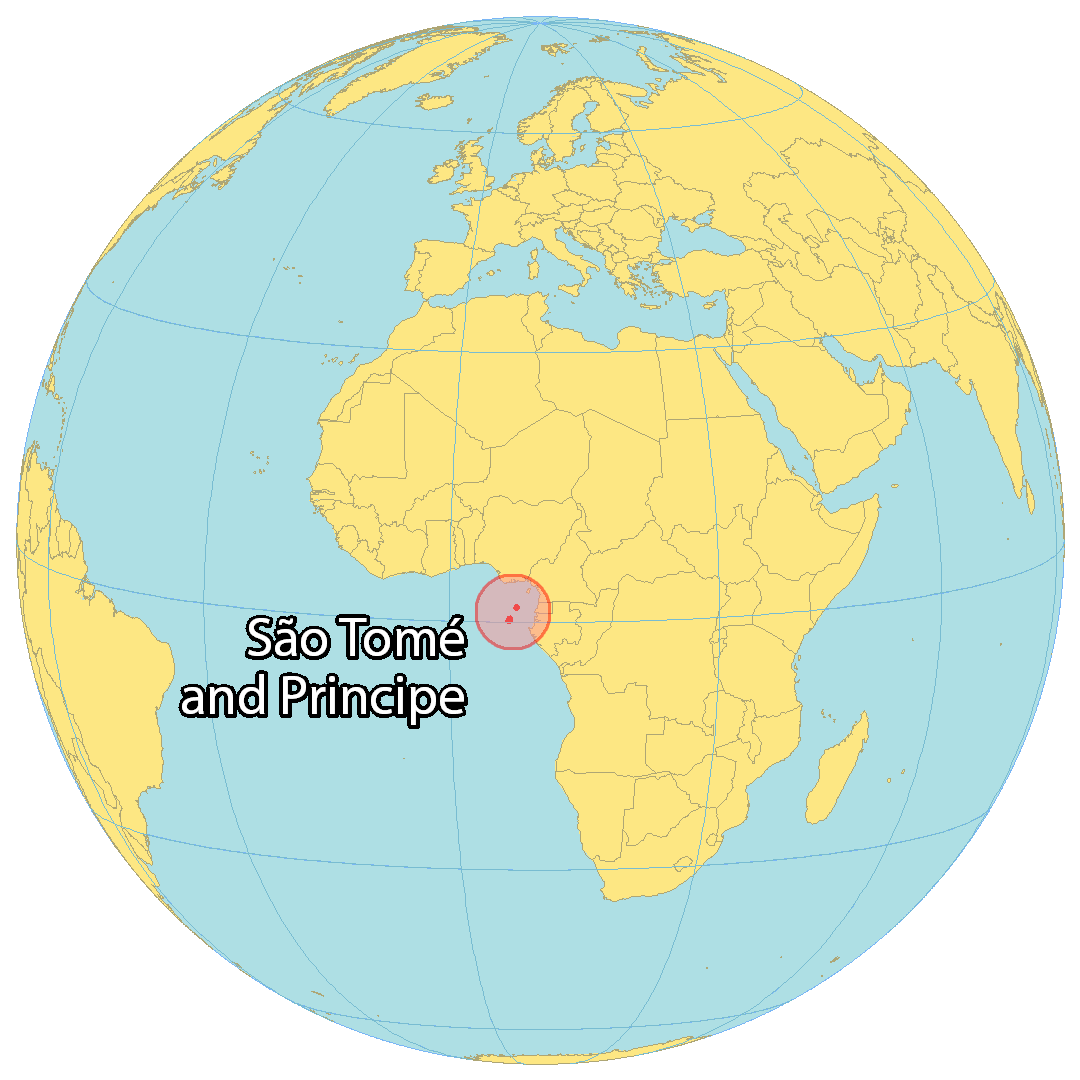

Where is São Tomé & Príncipe?

Sao Tome and Principe is a remarkable African island nation situated off the west coast, along the equator. It consists of two main islands, which are about 150 kilometers apart. The larger of the two is Sao Tome, located in the south and home to the nation’s capital city, Sao Tome. The smaller island of Principe is situated to the north and houses only 4% of the population. Additionally, there are several small islands in between the two main ones, such as Ilheu das Rolas, Ilhéu Caroço, the Cabras Islets, Tinhosa Grande and Tinhosa Pequena, which are all uninhabited. Other major cities of the nation include Santo Amaro, Neves, and Santana.

High Definition Political Map of São Tomé & Príncipe

History

Geological history

The islands making up São Tomé and Principe were formed around approximately 30 million years ago due to volcanic activity in deep water along the Cameroon Line. Over time, interactions with seawater and periods of eruption have engendered a wide variety of different igneous and volcanic rocks on the islands with complex assemblages of minerals.

Arrival of Europeans

The islands of São Tomé and Príncipe were uninhabited when the Portuguese arrived sometime around 1470. The first Europeans to put ashore were João de Santarém and Pêro Escobar. Portuguese navigators explored the islands and decided that they would be good locations for bases to trade with the mainland.

The dates of European arrival are sometimes given as 21 December (St Thomas’s Day) 1471, for São Tomé; and 17 January (St Antony’s Day) 1472, for Príncipe, though other sources cite different years around that time. Príncipe was initially named Santo Antão (“Saint Anthony”), changing its name in 1502 to Ilha do Príncipe (“Prince’s Island”), in reference to the Prince of Portugal to whom duties on the island’s sugar crop were paid.

The first successful settlement of São Tomé was established in 1493 by Álvaro Caminha, who received the land as a grant from the crown. Príncipe was settled in 1500 under a similar arrangement. Attracting settlers proved difficult, however, and most of the earliest inhabitants were “undesirables” sent from Portugal, mostly Sephardic Jews. 2,000 Jewish children, eight years old and under, were taken from the Iberian peninsula for work on the sugar plantations. In time, these settlers found the volcanic soil of the region suitable for agriculture, especially the growing of sugar.

Portuguese São Tomé and Príncipe

By 1515, São Tomé and Príncipe had become slave depots for the coastal slave trade centered at Elmina.

The cultivation of sugar was a labour-intensive process and the Portuguese began to enslave large numbers of Africans from the continent. In the sugar boom’s early stages, property on the islands had little value, with farming for local consumption while the economy relied mainly on the transit of slaves, though already many foodstuffs were imported. When the local landowner Álvaro Borges died in 1504, his cleared land and domesticated animals were sold for only 13,000 réis, about the price of three slaves. According to Valentim Fernandes around 1506, São Tomé had more sugarcane fields than Madeira “from which they already produce molasses,” but the island lacked facilities for industrial sugar production.

São Tomé would only become economically noteworthy with the introduction of a water-powered sugar mill in 1515, which soon led to the mass cultivation of sugar: “The fields are expanding and the sugar mills, too. At this time, only two sugar mills are here and another three are being built, counting the mill of the contractors, which is large. Similarly, the necessary conditions exist, such as streams and timber, to be able to build many more. And the [sugar] canes are the biggest I have ever seen in my life.” Sugar plantations were organized with slave labor, and by the mid-16th century, the Portuguese settlers had turned the islands into Africa’s foremost exporter of sugar.

Slaves in São Tomé were bought from the Slave Coast of West Africa, the Niger Delta, the island of Fernando Po, and later from the Kongo and Angola. In the 16th century, the enslaved were imported from and exported to Portugal, Elmina, the Kingdom of Kongo, Angola, and the Spanish Americas. In 1510, reportedly 10,000 to 12,000 slaves were imported by Portugal. In 1516, São Tomé received 4,072 slaves with the purpose of re-exportation. From 1519 to 1540, the island was the center of the slave trade between Elmina and the Niger Delta. Throughout the early to mid sixteenth century, São Tomé traded in slaves intermittently with Angola and the Kingdom of Kongo. In 1525 São Tomé began trafficking slaves to the Spanish Americas, mainly to the Caribbean and Brazil. From 1532 to 1536, São Tomé sent an annual average of 342 slaves to the Antilles. Prior to 1580, the island accounted for 75 percent of Brazil’s imports, mainly slaves. The slave trade remained a cornerstone of São Tomé’s economy until after 1600.

The power dynamics of São Tomé in the 16th century were surprisingly diverse with the participation of free mulatto[s] and black citizens in governance. Voluntary colonists shunned São Tomé for its disease and food shortages, so the Portuguese crown deported convicts to the island and encouraged interracial relationships to secure the colony. Slavery was also not permanent, as demonstrated through the 1515 royal decree granting the manumission of African wives of white settlers and their mixed-race children. In 1517, another decree freed the male slaves who had originally arrived on the island with the first colonists. After 1520, a royal charter allowed for property-owning, married, free mulattos to hold public offices. This was followed by a decree in 1546 establishing civil equality between these qualified mulattos and the white settlers, allowing free mulattos and black citizens opportunities for upward mobility and participation in local politics and business. Social divisions led to frequent disputes within the colony’s town councils and with the governor and bishop, with constant political unstability.

At first, slavery in São Tomé was less strict. In the mid-16th century, an anonymous Portuguese pilot noted that the slaves were employed as couples, built their own accommodations, and worked autonomously once a week on the cultivation of their own food supply. However, this more relaxed slave system did not last long following the introduction of plantations. Throughout, slaves frequently ran away to the inhospitable mountain forests of the island’s interior. Between 1514 and 1527, five percent of slaves that were imported to São Tomé escaped, often to starve, though 1531–1535 saw major food shortages even in the plantations. Eventually, the Maroon people developed settlements in the interior known as macambos.

The first signs of slave rebellion began in the 1530s, when the maroon gangs organized to attack plantations, some of which were abandoned. A formal complaint was lodged by local Portuguese authorities in 1531 lamenting that too many settlers and black citizens were being killed in the attacks, and that the island would be lost if the problem remained unresolved. In a 1533 ‘bush war’, a ‘bush captain’ led militia units to suppress the maroons. A significant event in the maroon fight for freedom occurred in 1549, when two men claiming to be free-born were taken in from the macambos by a wealthy mulatto planter named Ana de Chaves. With the support of de Chaves, the two men petitioned the king to be declared free, and the request was approved. The largest population of maroons coincided with the sugar boom of the mid-16th century, as the plantations teemed with slaves. Between 1587 and 1590, many of the runaway slaves were defeated in another bush war. By 1593, the governor declared the maroon forces almost completely extinguished. Nevertheless, maroon populations kept settlers away from the southern and western regions.

The greatest slave revolt occurred in July 1595, when the government was weakened by disputes between the bishop and the governor. A native slave named Amador recruited 5000 slaves to raid and destroy plantations, sugar mills, and settler houses. Amador’s rebellion made three raids on the town and destroyed 60 of the island’s 85 sugar mills, but they were defeated by the militia after three weeks. Two hundred slaves were killed in combat, and Amador and the other rebel leaders were executed, while the rest of the slaves were granted amnesty and returned to their plantation. Smaller slave rebellions followed in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Eventually, competition from sugar-producing colonies in the Western Hemisphere began to hurt the islands. The large enslaved population also proved difficult to control, with Portugal unable to invest many resources in the effort. Sugar cultivation thus declined over the next 100 years, and by the mid-17th century, São Tomé had become primarily a transit point for ships engaged in the slave trade between continental Africa and the Americas.

In the early 19th century, two new cash crops, coffee and cocoa, were introduced. The rich volcanic soils proved well suited to the new crops, and soon extensive plantations (known as roças), owned by Portuguese companies or absentee landlords, occupied almost all of the good farmland. By 1908, São Tomé had become the world’s largest producer of cocoa, which remains the country’s most important crop.

The roças system, which gave the plantation managers a high degree of authority, led to abuses against the African farm workers. Although Portugal officially abolished slavery in 1876, the practice of forced paid labour continued. Scientific American documented in words and pictures the continued use of slaves in São Tomé in its 13 March 1897 issue.

Observations of the solar eclipse of 29 May 1919 in Príncipe by Sir Arthur Eddington provided one of the first successful tests of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

In the early 20th century, an internationally publicized controversy arose over charges that Angolan contract workers were being subjected to forced labour and unsatisfactory working conditions. Sporadic labor unrest and dissatisfaction continued well into the 20th century, culminating in an outbreak of riots in 1953 in which several hundred African laborers were killed in a clash with their Portuguese rulers. The anniversary of this “Batepá Massacre” remains officially observed by the government.

Independence (1975)

By the late 1950s, when other emerging nations across the African continent demanded their independence, a small group of São Toméans formed the Movement for the Liberation of São Tomé and Príncipe (MLSTP), which eventually established its base in nearby Gabon. Picking up momentum in the 1960s, events moved quickly after the overthrow of the Caetano dictatorship in Portugal in April 1974.

The new Portuguese regime was committed to the dissolution of its overseas colonies. In November 1974, their representatives met with the MLSTP in Algiers and worked out an agreement for the transfer of sovereignty. After a period of transitional government, São Tomé and Príncipe achieved independence on 12 July 1975, choosing as the first president the MLSTP Secretary General Manuel Pinto da Costa.

In 1990, São Tomé became one of the first African countries to undergo democratic reform, and changes to the constitution – the legalization of opposition political parties – led to elections in 1991 that were nonviolent, free, and transparent. Miguel Trovoada, a former prime minister who had been in exile since 1986, returned as an independent candidate and was elected president. Trovoada was re-elected in São Tomé’s second multiparty presidential election in 1996.

The Party of Democratic Convergence won a majority of seats in the National Assembly, with the MLSTP becoming an important and vocal minority party. Municipal elections followed in late 1992, in which the MLSTP won a majority of seats on five of seven regional councils. In early legislative elections in October 1994, the MLSTP won a plurality of seats in the assembly. It regained an outright majority of seats in the November 1998 elections.

21st century

In the 2001 presidential elections the candidate backed by the Independent Democratic Action party, Fradique de Menezes, was elected in the first round and inaugurated on 3 September. Parliamentary elections were held in March 2002. For the next four years, a series of short-lived opposition-led governments was formed.

In July 2003 the army seized power for one week, complaining of corruption and that forthcoming oil revenues would not be divided fairly. An accord was negotiated under which President de Menezes was returned to office. in March 2006, the cohabitation period ended, when a propresidential coalition won enough seats in National Assembly elections to form a new government.

In the 30 July 2006 presidential election, Fradique de Menezes easily won a second five-year term in office, defeating two other candidates Patrice Trovoada (son of former President Miguel Trovoada) and independent Nilo Guimarães. Local elections, the first since 1992, took place on 27 August 2006 and were dominated by members of the ruling coalition. On 12 February 2009, a coup d’état was attempted to overthrow President Fradique de Menezes. The plotters were imprisoned, but later received a pardon from President de Menezes.

Evaristo Carvalho was the President of São Tomé and Príncipe since 2016 elections, after winning over the incumbent President Manuel Pinto da Costa. President Carvalho is also Vice president of the Independent Democratic Action party (ADI). Patrice Emery Trovoada was Prime Minister since 2014 and he is the leader of Independent Democratic Action party (ADI). In December 2018, Jorge Bom Jesus, the leader of the Movimento de Libertação de São Tomé e Príncipe-Partido Social Democráta (MLSTP-PSD), was sworn in as new prime minister.

In September 2021, the candidate of the centre-right opposition Independent Democratic Action (ADI), Carlos Vila Nova, won the presidential election.

In September 2022, the opposition Independent Democratic Action (ADI), led by former Prime Minister Patrice Trovoada, won the election over the ruling Movement for the Liberation of Sao Tome and Principe/Social Democratic Party (MLSTP/PSD) of Prime Minister Jorge Bom Jesus. In November of the same year, the government and military thwarted an attempted coup d’état. On 11 November 2022, Patrice Trovoada was appointed Prime Minister of São Tomé and Príncipe by the President of the Republic of São Tomé, Carlos Vila Nova.

Physical Map of São Tomé & Príncipe

Geography

The two islands that make up what is called São Tomé and Príncipe were formed 30 million years ago during the Oligocene era, due to volcanic activity beneath deep water along the Cameroon Line. The volcanic soils of basalts and phonolites, dating to 3 million years, have been used for plantation crops since colonial times.

The islands of São Tomé and Príncipe, situated in the equatorial Atlantic and Gulf of Guinea about 300 and 250 km (190 and 160 mi), respectively, off the northwest coast of Gabon, constitute Africa’s second-smallest country. Both are part of the Cameroon volcanic mountain line, which also includes the islands of Annobón to the southwest, Bioko to the northeast (both part of Equatorial Guinea), and Mount Cameroon on the coast of Gulf of Guinea. São Tomé is 50 km (30 mi) long and 30 km (20 mi) wide and the more mountainous of the two islands. Its peaks reach 2,024 m (6,640 ft) – Pico de São Tomé. Príncipe is about 30 km (20 mi) long and 6 km (4 mi) wide. Its peaks reach 948 m (3,110 ft) – Pico de Príncipe. Swift streams radiating down the mountains through lush forest and cropland to the sea cross both islands. The Equator lies immediately south of São Tomé Island, passing through the islet Ilhéu das Rolas.

The Pico Cão Grande (Great Dog Peak) is a landmark volcanic plug peak, at 0°7′0″N 6°34′00″E / 0.11667°N 6.56667°E / 0.11667; 6.56667 in southern São Tomé. It rises over 300 m (1,000 ft) above the surrounding terrain and the summit is 663 m (2,175 ft) above sea level.

Climate

The climate of S. Tomé and Príncipe is essentially conditioned by its geographic location, subject to the seasonal translation of low equatorial pressures, the monsoon winds from the south, the warm Guinea Current and the relief.

At sea level, the climate is tropical—hot and humid with average yearly temperatures of about 26 °C (78.8 °F) and little daily variation. The temperature rarely rises beyond 32 °C (89.6 °F). At the interior’s higher elevations, the average yearly temperature is 20 °C (68 °F), and nights are generally cool. Annual rainfall varies from 7,000 mm (275.6 in) in the highland cloud forests to 800 mm (31.5 in) in the northern lowlands. The rainy season is from October to May.

Biodiversity

The country’s territory is part of the São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón moist lowland forests ecoregion. It had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.64/10, ranking it 68th globally out of 172 countries. São Tomé and Príncipe does not have a large number of native mammals (although the São Tomé shrew and several bat species are endemic). The islands are home to a larger number of endemic birds and plants, including the world’s smallest ibis (the São Tomé ibis), the world’s largest sunbird (the giant sunbird), the rare São Tomé fiscal, and several giant species of Begonia. São Tomé and Príncipe is an important marine turtle-nesting site, including the hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata).