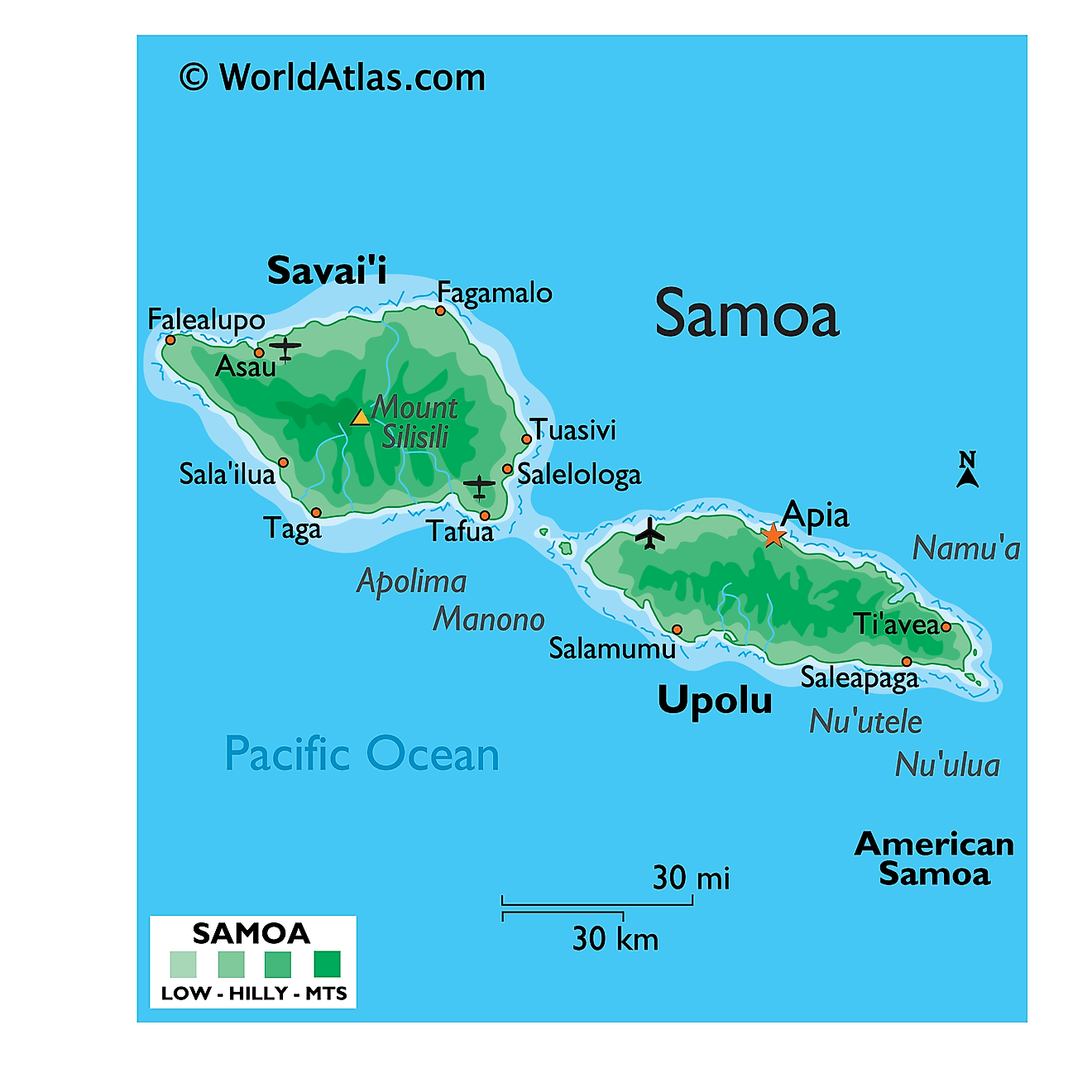

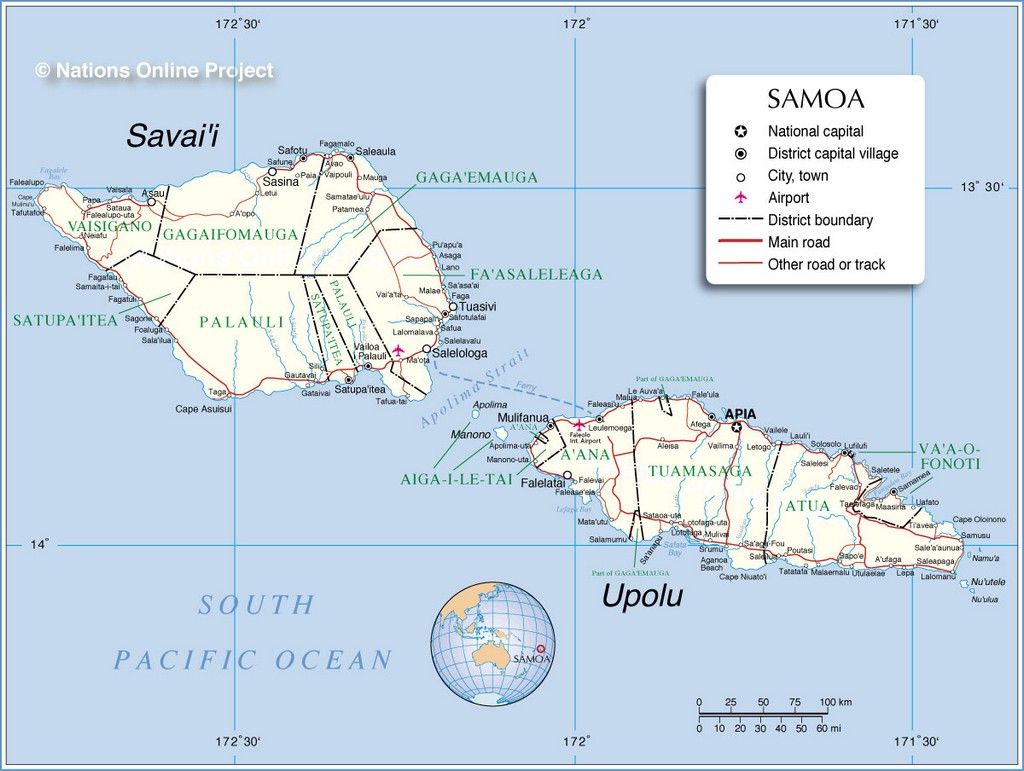

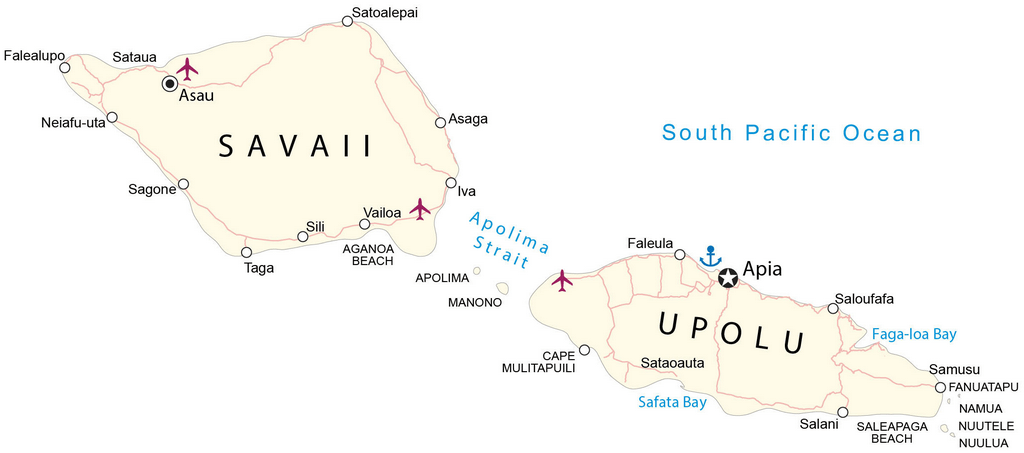

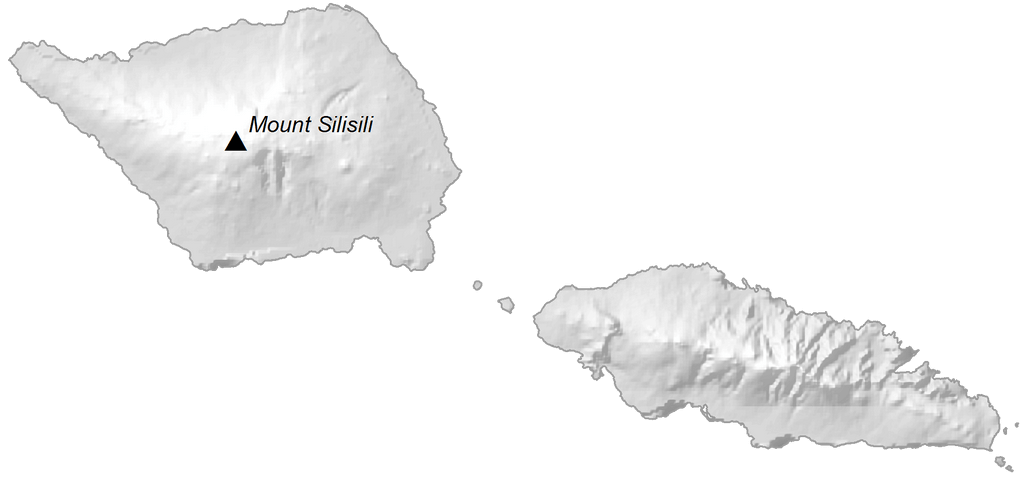

Covering an area of 2,842 sq.km (1,097 sq mi), Samoa is a Polynesian island nation comprising of two large islands of Saval ‘I and Upolu and 8 small islets namely, Manono Island, Apolima and Nu’ulopa; Nu’utele, Nu’ulua, Namua and Fanuatapu; and Nu’usafe’e; located in the South Pacific Ocean. Savai’i is Samoa’s largest island occupying about 1,707 sq.km area. Upolu is the 2nd largest island occupying an area of about 1,119 sq.km and is uneven in shape and more elongated than Savai’i. As observed on the physical map of Samoa above, the two large islands are mountainous, volcanic in origin and covered with heavy forests. The highest point is Mt. Sisisili on Savai’i Island which peaks at an elevation of 6,070ft (1,857m) and is marked on the map above by a yellow triangle. The islands are ringed by coral reefs and shallow lagoons.

Explore Samoa’s captivating geography with this stunning map! From the lush rainforests of Upolu to the rugged terrain of Savai’i, this map of Samoa showcases the nation’s varied landscape. See the towns, villages, roads, and waterways that crisscross the country, and use the satellite imagery and elevation map to observe the topography and volcanoes. Discover the beauty of Samoa with this interactive map!

Online Interactive Political Map

Click on ![]() to view map in "full screen" mode.

to view map in "full screen" mode.

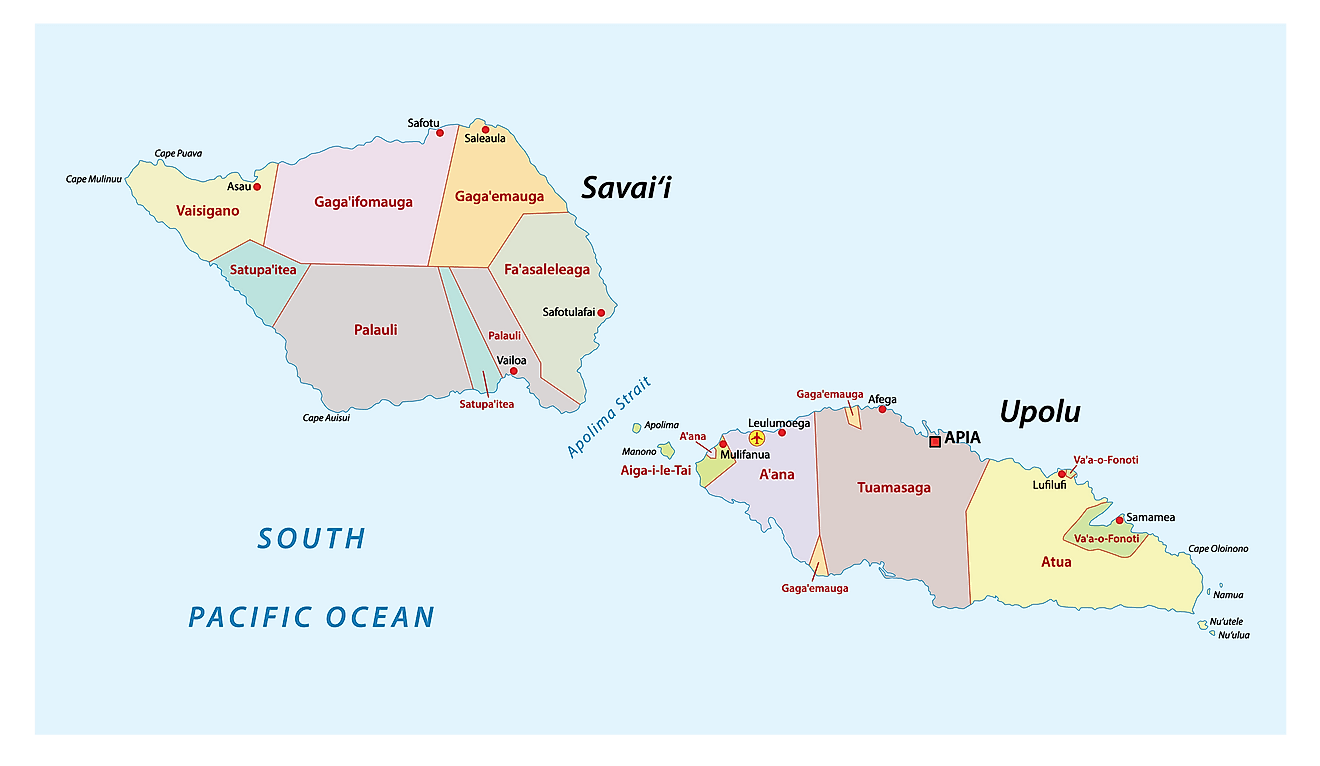

Samoa (officially, the Independent State of Samoa) is divided into 11 administrative districts. These districts are: A’ana, Aiga-i-le-Tai, Atua, Fa’asaleleaga, Gaga’emauga, Gagaifomauga, Palauli, Satupa’itea, Tuamasaga, Va’a-o-Fonoti and Vaisigano.

Covering an area of 2,842 sq.km, Samoa is a Polynesian island nation comprising of two large islands of Saval ‘I and Upolu and 8 small islets namely, Manono Island, Apolima and Nu’ulopa; Nu’utele, Nu’ulua, Namua and Fanuatapu; and Nu’usafe’e; located in the South Pacific Ocean.

Located on the northern coast of Upolu Island, on a natural harbor at the mouth of Vaisigano River is, Apia – the capital and the largest city of Samoa. It serves as the main port and the administrative and commercial center in Samoa.

Location Maps

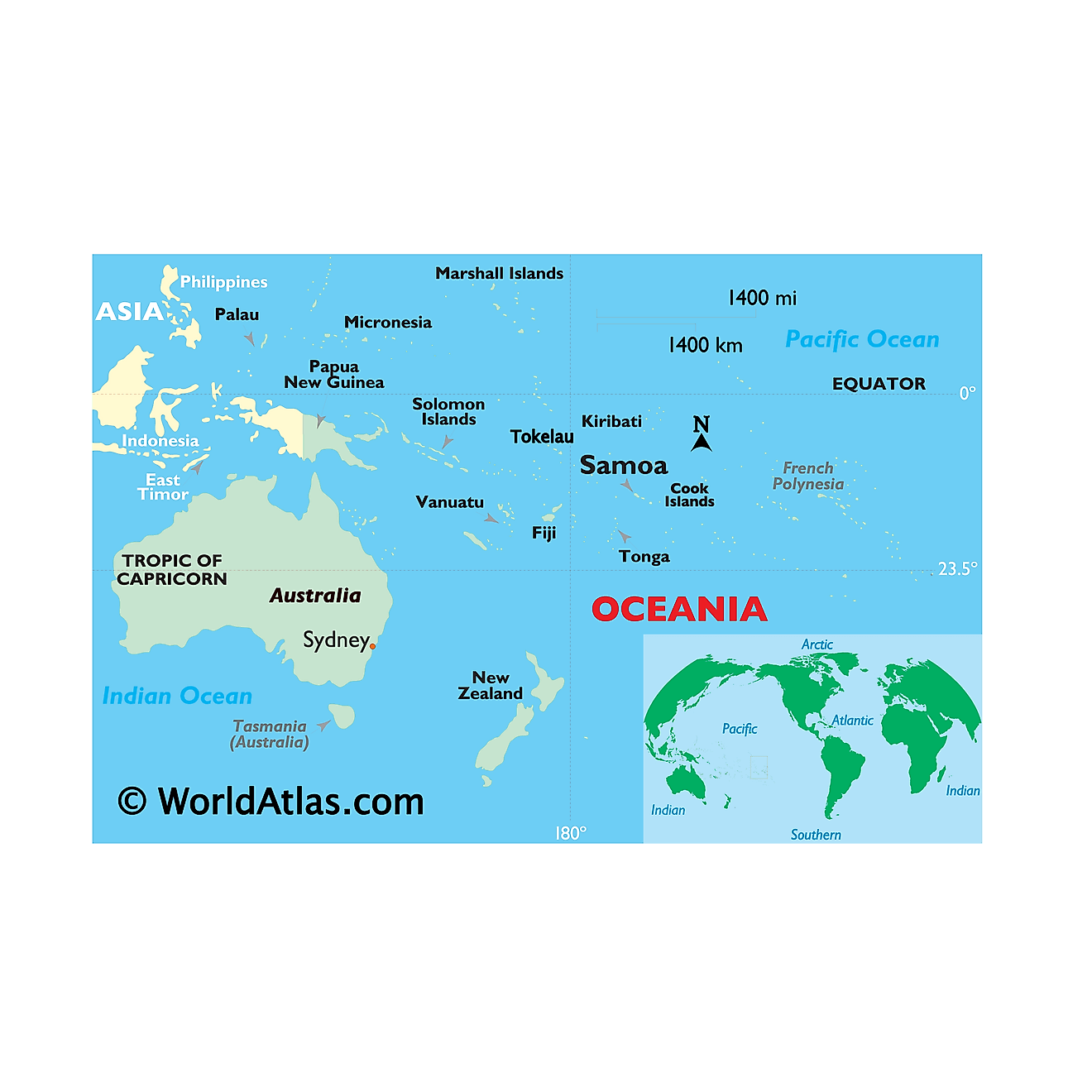

Where is Samoa?

Samoa is an archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean, located halfway between Hawaii and New Zealand. The two main islands are Savaii and Upolu, which are home to the capital city of Apia. Mount Silisili, the highest peak in Samoa, is located on Savaii Island. Upolu Island is a basaltic shield volcano that houses Faleolo International Airport. Other major towns are Asau, Mulifanua, and Faleula.

High Definition Political Map of Samoa

History

Early history

Samoa was discovered and settled by the Lapita people (Austronesian people who spoke Oceanic languages), who travelled from Island Melanesia. The earliest human remains found in Samoa are dated to between roughly 2,900 and 3,500 years ago. The remains were discovered at a Lapita site at Mulifanua, and the scientists’ findings were published in 1974. The Samoans’ origins have been studied in modern times through scientific research on Polynesian genetics, linguistics and anthropology. Although this research is ongoing, a number of theories have been proposed. One theory is that the original Samoans were Austronesians who arrived during a final period of eastward expansion of the Lapita peoples out of Southeast Asia and Melanesia between 2,500 and 1,500 BCE.

Intimate sociocultural and genetic ties were maintained between Samoa, Fiji, and Tonga, and the archaeological record supports oral tradition and native genealogies that indicate interisland voyaging and intermarriage among precolonial Samoans, Fijians, and Tongans. Notable figures in Samoan history included the Tui Manu’a line, Queen Salamasina, King Fonoti and the four tama-a-aiga: Malietoa, Tupua Tamasese, Mata’afa, and Tuimalealiifano. Nafanua was a famous woman warrior who was deified in ancient Samoan religion and whose patronage was highly sought after by successive Samoan rulers.

Today, all of Samoa is united under its two principal royal families: the Sā Malietoa of the ancient Malietoa lineage that defeated the Tongans in the 13th century; and the Sā Tupua, Queen Salamasina’s descendants and heirs who ruled Samoa in the centuries that followed her reign. Within these two principal lineages are the four highest titles of Samoa – the elder titles of Malietoa and Tupua Tamasese of antiquity and the newer Mata’afa and Tuimalealiifano titles, which rose to prominence in 19th-century wars that preceded the colonial period. These four titles form the apex of the Samoan matai system as it stands today.

Contact with Europeans began in the early 18th century. Jacob Roggeveen, a Dutchman, was the first known non-Polynesian to sight the Samoan islands in 1722. This visit was followed by French explorer Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, who named them the Navigator Islands in 1768. Contact was limited before the 1830s, which is when English missionaries, whalers, and traders began arriving.

19th century

Visits by American trading and whaling vessels were important in the early economic development of Samoa. The Salem brig Roscoe (Captain Benjamin Vanderford), in October 1821, was the first American trading vessel known to have called, and the Maro (Captain Richard Macy) of Nantucket, in 1824, was the first recorded United States whaler at Samoa. The whalers came for fresh drinking water, firewood and provisions, and later, they recruited local men to serve as crewmen on their ships. The last recorded whaler visitor was the Governor Morton in 1870.

Christian missionary work in Samoa began in 1830 when John Williams of the London Missionary Society arrived in Sapapali’i from the Cook Islands and Tahiti. According to Barbara A. West, “The Samoans were also known to engage in ‘headhunting’, a ritual of war in which a warrior took the head of his slain opponent to give to his leader, thus proving his bravery.”

In A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa (1892), Robert Louis Stevenson details the activities of the great powers battling for influence in Samoa – the United States, Germany and Britain – and the political machinations of the various Samoan factions within their indigenous political system. Even as they descended into ever greater interclan warfare, what most alarmed Stevenson was the Samoans’ economic innocence. In 1894, just months before his death, he addressed the island chiefs:

He had “seen these judgments of God” in Hawaii, where abandoned native churches stood like tombstones “over a grave, in the midst of the white men’s sugar fields”.

The Germans, in particular, began to show great commercial interest in the Samoan Islands, especially on the island of Upolu, where German firms monopolised copra and cocoa bean processing. The United States laid its own claim, based on commercial shipping interests in Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and Pago Pago Bay in eastern Samoa, and forced alliances, most conspicuously on the islands of Tutuila and Manu’a, which became American Samoa.

Britain also sent troops to protect British business enterprise, harbour rights, and consulate office. This was followed by an eight-year civil war, during which each of the three powers supplied arms, training and in some cases combat troops to the warring Samoan parties. The Samoan crisis came to a critical juncture in March 1889 when all three colonial contenders sent warships into Apia harbour, and a larger-scale war seemed imminent. A massive storm on 15 March 1889 damaged or destroyed the warships, ending the military conflict.

The Second Samoan Civil War reached a head in 1898 when Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States were locked in dispute over who should control the Samoan Islands. The Siege of Apia occurred in March 1899. Samoan forces loyal to Prince Tanu were besieged by a larger force of Samoan rebels loyal to Mata’afa Iosefo. Supporting Prince Tanu were landing parties from four British and American warships. After several days of fighting, the Samoan rebels were finally defeated.

American and British warships shelled Apia on 15 March 1899, including the USS Philadelphia. Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States quickly resolved to end the hostilities and divided the island chain at the Tripartite Convention of 1899, signed at Washington on 2 December 1899 with ratifications exchanged on 16 February 1900.

The eastern island-group became a territory of the United States (the Tutuila Islands in 1900 and officially Manu’a in 1904) and was known as American Samoa. The western islands, by far the greater landmass, became German Samoa. The United Kingdom had vacated all claims in Samoa and in return received (1) termination of German rights in Tonga, (2) all of the Solomon Islands south of Bougainville, and (3) territorial alignments in West Africa.

German Samoa (1900–1914)

The German Empire governed the western part of the Samoan archipelago from 1900 to 1914. Wilhelm Solf was appointed the colony’s first governor. In 1908, when the non-violent Mau a Pule resistance movement arose, Solf did not hesitate to banish the Mau leader Lauaki Namulau’ulu Mamoe to Saipan in the German Northern Mariana Islands.

The German colonial administration governed on the principle that “there was only one government in the islands.” Thus, there was no Samoan Tupu (king), nor an alii sili (similar to a governor), but two Fautua (advisors) were appointed by the colonial government. Tumua and Pule (traditional governments of Upolu and Savai’i) were for a time silent; all decisions on matters affecting lands and titles were under the control of the colonial Governor.

In the first month of World War I, on 29 August 1914, troops of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force landed unopposed on Upolu and seized control from the German authorities, following a request by Great Britain for New Zealand to perform this “great and urgent imperial service.”

New Zealand rule (1914–1961)

From the end of World War I until 1962, New Zealand controlled Western Samoa as a Class C Mandate under trusteeship through the League of Nations, then through the United Nations. Between 1919 and 1962, Samoa was administered by the Department of External Affairs, a government department which had been specially created to oversee New Zealand’s Island Territories and Samoa. In 1943, this department was renamed the Department of Island Territories after a separate Department of External Affairs was created to conduct New Zealand’s foreign affairs. During the period of New Zealand control, their administrators were responsible for two major incidents.

In the first incident, approximately one fifth of the Samoan population died in the influenza epidemic of 1918–1919.

In 1918, during the final stages of World War I, the Spanish flu had taken its toll, spreading rapidly from country to country. On Samoa, there had been no epidemic of pneumonic influenza in Western Samoa before the arrival of the SS Talune from Auckland on 7 November 1918. The NZ administration allowed the ship to berth in breach of quarantine; within seven days of this ship’s arrival, influenza became epidemic in Upolu and then spread rapidly throughout the rest of the territory. Samoa suffered the most of all Pacific islands, with 90% of the population infected; 30% of adult men, 22% of adult women and 10% of children died. The cause of the epidemic was confirmed in 1919 by a Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Epidemic concluded that there had been no epidemic of pneumonic influenza in Western Samoa before the arrival of the Talune from Auckland on 7 November 1918.

The pandemic undermined Samoan confidence in New Zealand’s administrative capacity and competence. Some Samoans asked that the rule of the islands be transferred to the Americans or the British.

The second major incident arose out of an initially peaceful protest by the Mau (which literally translates as “strongly held opinion”), a non-violent popular movement which had its beginnings in the early 1900s on Savai’i, led by Lauaki Namulauulu Mamoe, an orator chief deposed by Solf. In 1909, Lauaki was exiled to Saipan and died en route back to Samoa in 1915.

By 1918, Western Samoa had a population of some 38,000 Samoans and 1,500 Europeans.

However, native Samoans greatly resented New Zealand’s colonial rule, and blamed inflation and the catastrophic 1918 flu epidemic on its misrule. By the late 1920s the resistance movement against colonial rule had gathered widespread support. One of the Mau leaders was Olaf Frederick Nelson, a half Samoan and half Swedish merchant. Nelson was eventually exiled during the late 1920s and early 1930s, but he continued to assist the organisation financially and politically. In accordance with the Mau’s non-violent philosophy, the newly elected leader, High Chief Tupua Tamasese Lealofi, led his fellow uniformed Mau in a peaceful demonstration in downtown Apia on 28 December 1929.

The New Zealand police attempted to arrest one of the leaders in the demonstration. When he resisted, a struggle developed between the police and the Mau. The officers began to fire randomly into the crowd and used a Lewis machine gun, mounted in preparation for the demonstration, to disperse the demonstrators. Mau leader and paramount chief Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III was shot from behind and killed while trying to bring calm and order to the Mau demonstrators. Ten others died that day and approximately 50 were injured by gunshot wounds and police batons. That day would come to be known in Samoa as Black Saturday.

On 13 January 1930, the New Zealanders banned the organisation. As many as 1500 Mau men took to the bush, pursued by an armed force of 150 marines and seamen from the light cruiser HMS Dunedin, and 50 military police. Villages were raided, often at night and with fixed bayonets. In March, through the mediation of local Europeans and missionaries, Mau leaders met New Zealand’s Minister of Defence and agreed to disperse.

Supporters of the Mau continued to be arrested, so women came to the fore rallying supporters and staging demonstrations. The political stalemate was broken following the victory of the Labour Party in New Zealand’s 1935 general election. A ‘goodwill mission’ to Apia in June 1936 recognised the Mau as a legitimate political organisation, and Olaf Nelson was allowed to return from exile. In September 1936, Samoans exercised for the first time the right to elect the members of the advisory Fono of Faipule, with representatives of the Mau movement winning 31 of the 39 seats.

Independence

After repeated efforts by the Samoan independence movement, the New Zealand Western Samoa Act 1961 of 24 November 1961 terminated the Trusteeship Agreement and granted the country independence as the Independent State of Western Samoa, effective on 1 January 1962. Western Samoa, the first small-island country in the Pacific to become independent, signed a Treaty of Friendship with New Zealand later in 1962. Western Samoa joined the Commonwealth of Nations on 28 August 1970. While independence was achieved at the beginning of January, Samoa annually celebrates 1 June as its independence day.

On 15 December 1976, Western Samoa was admitted to the United Nations as the 147th member state. It asked to be referred to in the United Nations as the Independent State of Samoa.

Travel writer Paul Theroux noted marked differences between the societies in Western Samoa and American Samoa in 1992.

On 4 July 1997 the government amended the constitution to change the name of the country from Western Samoa to Samoa, the name it had been called by in the United Nations since it joined. American Samoa protested against the name change, asserting that it diminished its own identity.

In 2002, New Zealand prime minister Helen Clark formally apologised for New Zealand’s role in the Spanish influenza outbreak in 1918 that killed over a quarter of Samoa’s population and for the Black Saturday killings in 1929.

On 7 September 2009, the government changed the rule of the road from right to left, in common with most other Commonwealth countries – most notably countries in the region such as Australia and New Zealand, home to large numbers of Samoans. This made Samoa the first country in the 21st century to switch to driving on the left.

At the end of December 2011, Samoa changed its time zone offset from UTC−11 to UTC+13, effectively jumping forward by one day, omitting Friday, 30 December from the local calendar. This also had the effect of changing the shape of the International Date Line, moving it to the east of the territory. This change aimed to help the nation boost its economy in doing business with Australia and New Zealand. Before this change, Samoa was 21 hours behind Sydney, but the change means it is now three hours ahead. The previous time zone, implemented on 4 July 1892, operated in line with American traders based in California. In October 2021, Samoa ceased daylight saving time.

In 2017, Samoa signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

In June 2017, Parliament amended Article 1 of the Samoan Constitution to make Christianity the state religion.

In May 2021, Fiamē Naomi Mataʻafa became Samoa’s first female prime minister. Mataʻafa’s FAST party narrowly won the election, ending the rule of long-term Prime Minister Tuila’epa Sa’ilele Malielegaoi of the Human Rights Protection Party (HRPP), although the constitutional crisis complicated and delayed this. On 24 May 2021, she was sworn in as the new prime minister, though it was not until July that the Supreme Court ruled that her swearing-in was legal, thus ending the constitutional crisis and bringing an end to Tuila’epa’s 22-year premiership. The FAST party’s success in the 2021 election and subsequent court rulings also ended nearly four decades of HRPP rule.

In August 2022, Samoa’s Legislative Assembly reappointed Tuimaleali’ifano Vaaletoa Sualauvi II as the Head of State for a second term of five years.

Physical Map of Samoa